Photograph by Amy Lepine PetersonThis summer my husband and I bought our first home, and the process of moving into it just about did me in. I should have been prepared. After all, I had moved six times in my twenties, across oceans and continents, my life fluid and free. Back then I fancied myself an unmaterialistic backpacking goddess, proud that possessions never possessed me, my belongings slipping through my fingers like water.

Photograph by Amy Lepine PetersonThis summer my husband and I bought our first home, and the process of moving into it just about did me in. I should have been prepared. After all, I had moved six times in my twenties, across oceans and continents, my life fluid and free. Back then I fancied myself an unmaterialistic backpacking goddess, proud that possessions never possessed me, my belongings slipping through my fingers like water.

When Jack and I married, we hardly registered for anything — “Do we really need that?” we’d ask — and we settled into our 600-square-foot apartment with hand-me-downs and gracious gifts from friends. A year later we sold all but what fit into a storage cube — practically everything but our books and our bed had to go — and drove to Seattle, where we lived in one bedroom of a shared home for international students. After three years of communal living, we moved into an average-sized house in Indiana and marveled at all the empty space we needed to fill. That was our rental home, and for three years we filled it: an enormous baroque mirror for one wall, mid-century wooden side tables from an estate sale, chocolate-brown sofas hauled over from the yard sale across the road.

So last month as I found myself searching for the right cardboard box to hold some of our hundred-or-so LPs for the move across town, twisting sweaty strands of brown hair into a top knot while the Indiana heat began to concentrate in my house, I had to wonder how I’d gotten here. How did I have so much stuff? Had my footloose, fancy-free, wanderlusting self died when I turned thirty? Was motherhood to blame? Had I turned into one of those materialistic, over-consuming American adults I used to despise?

Not all of our consumption had been thoughtful (the brown sofa testifies loudly to that truth). The records, though — they were there on purpose. Stacking Sufjan Stevens next to Simon and Garfunkel, I thought about our reasons for owning the records. We hadn’t bought them because they sounded better (experts debate that claim, anyway). We hadn’t bought them out of nostalgia — records just barely made it onto the edges of our earliest music memories as we had been brought up on cassette tapes. Maybe the tapes are a good way to explain our decision, though.

I can still remember the first tape that I loved. It was Rich Mullins’s Winds of Heaven, Stuff of Earth, and I was probably about ten years old when I got it. I had some CDs too — ones I got free because my dad worked at a radio station — like Amy Grant's Heart in Motion (signed picture included) and Steven Curtis Chapman's Great Adventure. Around the time I graduated from high school, technology changed again. We had Napster, and I was hunting down new things —mp3 files burned to disc: Rosie Thomas, Dar Williams, REM, the Indigo Girls, Toad the Wet Sprocket.

But the tapes, which I played in my '88 Camry — the tapes were what I loved. I worked for them. I took a blank tape over to the house where I was babysitting so that after the kids fell asleep, I could carefully set up their parents’ boombox to copy their Hootie and the Blowfish album from CD. I collected the recordings Caedmon's Call made before they were signed to a label. I memorized Joni Mitchell’s Hits.

Through all the technological changes, my listening was always limited to the collection that I owned, and as I result, I really treasured albums, listening to almost all of them until I knew all the words by heart (a little embarrassing later in life, especially the Hootie and the Blowfish part). The music shaped me.

When in my twenties isoHunt appeared, my husband and I indulged in peer-to-peer sharing for a few years; and then Pandora, and then Rdio and Spotify; and I could listen to (or even "own") almost anything I wanted, at any time, and in practically any place. Our computer was filled up with mp3s we’d paid nothing for and had listened to maybe once.

Until one day when my husband suggested that we needed to stop. Partly, it was the legality (peer-to-peer sharing might be less than legal), and partly, it was the morality (Spotify pays its artists next to nothing), but mostly, it was about the music.

Music had been meaningful throughout our lives, a source of hope and creative inspiration and commiseration and joy. But now, the abundant availability was actually making it harder to appreciate or be moved by the songs we listened to. Music wasn't worth as much. So it didn't mean as much. I couldn’t have recited the lyrics or hummed the melody to half of those songs on our hard drive; many of them, I might not have even recognized. The music we had was digital, taking up no space in my life at all. It was overconsumption of something that was as light as air, and it meant nothing.

My husband was right. I wanted music to mean something to me again. I wanted particular albums to shape me the way Rich Mullins had when I listened to that tape over and over again with my headphones and Walkman, staring out the window of the backseat of the car on family vacation. For music to mean something, I would have to have less of it.

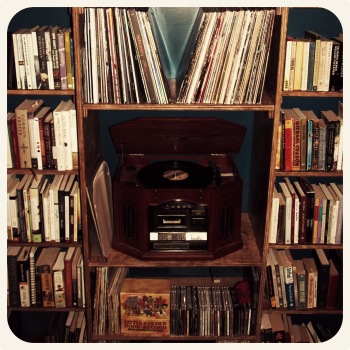

We deleted most of the files on the computer. I bought Jack a record player for his birthday, and we began slowly purchasing the albums we really loved on vinyl. Now, when we get new music, it’s an investment — something we’re willing to pay for and make space in our house for. Because of that, we also invest our time listening to it and letting it grow space in our hearts.

Recently I've felt that listening to music on a record player is something like the liturgy at our Episcopal church. Listening to a record is a physical process. I don't type a name in a search box; I kneel and flip through record sleeves. I stand, and lift the lid, and place the needle just right. The music requires attention, and after a few songs, I move to turn the record over. The records, and the player, take up physical space in my life — a rooted kind of space. They require a physical response, and like the prayers at church, they are repeated. Place and posture, roots and response, attention and repetition: these not only signal that what I'm doing means something, but that it is creating meaning as well.

Maybe my past self was a bit of a gnostic, treating physical possessions as if they were inherently evil, traveling light because I was h-h-h-heavenbound (DC Talk, anyone?). This week, after two months in our new house, we finally unpacked our record collection. Jack had just finished building custom bookshelves to hold the albums, and we put on The Mountain Goats, poured some wine, and started filling the empty spaces with the very good gifts of God.

Amy Lepine Peterson teaches American Pop Culture and ESL Writing at Taylor University, and blogs at Making All Things New.