It’s spring cleaning time (by which I mean rediscovering-what’s-been-shoved-to-the-back-of-the-closet time), and memories pile up like fabric strips for an unpieced quilt ...

The first quilt my mother completed was a lap robe for Aunt Winnie, a cousin of my grandmother’s, after she moved from the two-story house she had shared with her sister into a nursing home in our small Ohio town. There’s evidence of mom’s pride in her completed work: a series of photographs of it indoors, spread across the sofa, and outdoors, draped over a long bench on our deck, its diamond patchwork colors like soft jewels in the sunlight. “Winnie Brown / Made by Linda G. Brown, 1988” reads the provenance on the backside, hand-lettered on iron-on oval patches.

The second quilt she completed was for my toddler cousin Alyson, daughter of mom’s middle brother in his second marriage. If there are photos of this quilt, I don’t remember seeing them. This time she embroidered the “made by” information on a square of muslin, but up against the deadline of their brief visit from four states away, she didn’t have time to whip-stitch it onto the quilt before giving the gift to his family. She instructed my new aunt about how to complete that task, but she fretted privately that it would never be done.

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

The third quilt she worked on was finally one for her own bed. She chose a modified Irish chain pattern, using only three fabrics with delicate floral designs, appliqued with peach-pink hearts. It was pieced, assembled with batting and backing, and she slowly quilted it by hand, sitting in her TV-watching spot on the left side of the love seat, next to the good lamp.

Mom died suddenly at age 50, when a weakened mitral valve gave out. April 1989. A few weeks past my 28th birthday, a few weeks shy of her 29th wedding anniversary. Gone in a heartbeat.

In the weeks and months after her funeral, my brother and I helped dad sort through her things. When I moved South two years later, I took much of her fabric stockpiles with me, along with a shelf-load of quilting books, wooden hoops, needles and thimbles, templates, and some odds and ends I didn’t even know what to do with. She had left no will, and I regarded these materials of the craft as my inheritance. That partly completed quilt came with me too, sewn up with dad’s grief-stitched prediction, “You won’t finish that.”

Sifting through the bits of cloth a quilter leaves behind is emotional archaeology, an imperfect dig: part discovery, part guesswork, part revising hypotheses over time, but mostly making peace with unknowing.

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

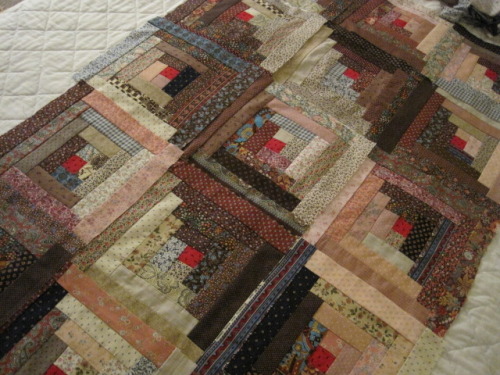

A partial inventory: hundreds of carefully cut squares, in different sizes, from dozens of fabrics. A shoebox full of long strips for a log cabin quilt. Five quilt squares, each in a different standard pattern, possibly for a sampler quilt. Unsewn pieces of peach cloth for a baby’s dress with a handsmocked yoke. Penciled notes on irregular bits of muslin.

I’ve carted that fabric a thousand miles, through two moves and 20 years. Some of it went into quilts I made in the 1990s for a new love, a coworker’s baby, and mom’s younger brother. Some went into pillows, table runners, a potholder. And some became clothing and doll accessories for my own daughter, whom mom never met. Much of it — including some wildly patterned material from the ’60s and ’70s — I donated to a friend’s quilting circle. Some of those funky retro prints, I was later told, eventually found their way into a student-made quilt project at Westside Middle School in northeast Arkansas, where two little boys massacred some of their classmates. Grief and anger and fear and speechlessness remade, their classmates remembered, through the work of their hands.

And the rest — there it still is, in plastic bins and milk crates in the back of my closet. There’s a scrap from the yoke of the summer dress I liked to wear with espadrilles when I was a teenager, and an irregular remnant from the shirt-blouse-vest trio mom made for a solo flute performance my senior year. Those outfits are long gone, but these bits and pieces remain, their colors just as vibrant, their potential just as strong for refashioning into something both utilitarian and beautiful.

On the day before Mother’s Day, during my weekly phone date with my father, the subject of quilting came up. My brother had taken one of mom’s unfinished quilts and eventually finished it, he said. And the one she was making for their bed — had I ever finished it?

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown“It’s on my bed now,” I said. I made some progress on it, I told him, and then a few years ago for Christmas, the extended family I had made here in Arkansas surprised me by smuggling it out of the house and having it finished by a Methodist church’s quilting circle. One quilter was a friend I played music with; lots of people were involved in keeping that secret, and in bearing my delight afterward.

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown“It’s on my bed now,” I said. I made some progress on it, I told him, and then a few years ago for Christmas, the extended family I had made here in Arkansas surprised me by smuggling it out of the house and having it finished by a Methodist church’s quilting circle. One quilter was a friend I played music with; lots of people were involved in keeping that secret, and in bearing my delight afterward.

I told him that when we gathered to open gifts that Christmas morning, I had set a box of Kleenex nearby, “in case anyone’s overcome with emotion.” When I opened that large soft bundle and saw those familiar patchwork hearts, I was the one who needed the tissue.

At the same time I told him that that was one of the best Christmas gifts anyone ever gave me, Dad said something I didn’t catch at first. His voice was tender with tears. I don’t know for sure, but I think he understood in a way he never had before that I and my people here had stitched each other into the fabric of our lives. And I understood in a way I never had that the quilt, intended for their marital bed, must have represented her loss all over again. The way it looked must have faded into a threadbare memory for him, the way the sound of her voice has dimmed for me.

Those unfinished projects no longer seem tragic. They’re comforting evidence that, like me, like all of us, mom lived with gaps between intention and fruition. I have the choice, and the privilege, but not the obligation, to finish some of what she started. Though I am my mother’s uncompleted work, I think she would approve. And when dad closes our conversation with “Love you, babe” — a word he often used for her, but seldom for me — it comes as a benediction. Somehow we are weaving whole cloth of the threads she left behind.

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

Photo: Laura Lynn Brown

It’s spring cleaning time (by which I mean do-something-with-what’s-been-shoved-to-the-back-of-the-closet time), and lo and behold, there are those strips she cut for a log cabin quilt, separated into light and dark, and there are the 20 log cabin squares I completed sometime in the last millennium. I flip mom’s quilt over on my bed and use its muslin backing as a blank canvas to lay the squares out in possible patterns.

Laura Lynn Brown loves the sounds of a coffee maker brewing, a baseball game on the radio, and her mother’s Singer console sewing machine. She lives, writes, and occasionally sews in Little Rock, Arkansas.