There is a specific clamor that accompanies a real fight, the kind where two people hit and claw out of sheer passion and pain. It’s the cheer from a football stadium meshed with a tornado siren, a shrill energy of anticipation and fear. I heard it a few months ago as I stood in my public high school classroom and tried to wrap up the day. I wanted to go home and get to my own work of writing my novel. But novel or no, there was no decision when I heard the fight. My size and strength didn’t matter; I called for help and ran. Even as I sprinted toward the sound, my head told me, “Go faster,” and at the same time, “Be careful.”

I rounded the corner of the stairwell and barely skidded to a stop in front of two girls. I was the first teacher to arrive; students were still running up. The throng of kids quickly trapped me in the middle of the circle while bodies much larger than mine bumped and pushed toward the flying nails and blood to get a better look at the action. One of my own students pushed me out of his way, and I had to restrain myself from jabbing his gut with my elbow in self-defense. A mass of yelling and screaming students, anxious to witness the action, jostled me to the very center, where just a few feet remained open for the sparring teenagers.

They were evenly matched and about my size. The fine gold and copper braids of the black girl just in front of me, flying metallic waves of gorgeous hair, swung as she moved from side to side. Her hands were on her opponent, an olive-skinned girl with a broad face, eyes wide and black. Those eyes looked too open, too round. Bloody red fingerprints, some pressed hard and dark, others barely grazing the surface, stained like paint on vellum so that I could see her lovely skin shine through the scarlet swirls.

I pushed onlookers back, holding my arms outstretched and pressing back towards the doors – partly to defray the mob, but mainly to protect my body from those fingerprints. Like waves push in the ocean, children too caught up in the moment rubbed against me, and I had to put one leg behind me and lock it to keep out of the fray. Thankfully, I was quickly joined by three teacher aids, who successfully pulled the two apart. The young women both cried as they were escorted to the office. No longer two rabid creatures but two lost daughters walking side-by-side in a hallway while students and teachers alike stared and shook their heads. The fight was over. Now, once my heart quit racing, I could go home.

It’s true what they say about girls and fighting, I thought. While I’d broken up several fights between boys, even between rival gang members, I couldn’t break up the girls. Girls fight because a wrong has been done to them. They fight in public to set a precedent – to openly determine the truth about who is right and who’s been wronged. They fight out of pain, desire, and a true sense of loss. And they don’t stop. As I stood in the middle of the circle, pushed into the two young women by the crowd, I knew that I could not restrain them alone. The fingerprints — each personally unique print on the olive face – haunted me. I saw the whorls and designs of each as an individual — prints that no one else in the history of the world would have. They marked her, like Annie Dillard’s cat, and I was afraid.

The next day my students cheered me in class for having broken up the fight. They too had run to witness the fight, but not to stop it. Even my honors students savored the sight of two people tearing one another apart. They championed me as their victor, and I was embarrassed by their acclaim, and ashamed of my own fear. Their delight angered me; these, my college-bound favorites, delighted in the thrill of open pain.

“Why did you watch it?” I asked them. “Why didn’t you just go home?”

“We have nothing else,” a boy answered. A good boy. A smart boy. I thought about the radio stations that shuffle through the same club and hook-up songs. I considered how much television relies on reality setups and crime shows based on sexual assault. And then I looked at my classroom’s white walls and gray tile, specially chosen for thrift rather than inspiration. I saw thirty-four faces nodding in agreement. And I felt like I had nothing else. I wanted to go home and take a bath. Though my novel waited for me at the house, I told myself that I was too tired and too sad to create a world of beauty.

But at home again, I walked my dog, and I looked at live oak trees that stay green throughout the winter. I made noisy progress along a sidewalk covered with acorns and crunched each foot down to satisfyingly destroy the kernels below me. I was still tired, but I was also reminded that my students yearn, as all people yearn, for truth and beauty. Because they lack it. “For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God (Romans 8:19)." Out of their poverty, they substitute the truth for a lie, because the lie is all they know, yet they search for truth where they can. They glory at the honesty of bloody fingerprints on otherwise radiant skin; they revel at locks of hair torn and then thrown to the grimy ground. They rejoice in meaning, even when it’s ugly. They acknowledge desire, fear, passion, angst, and ache to see it with their own eyes.

In teaching this mob I sometimes wonder if it’s worth sacrificing my own writing time to tutor, to hold detentions, to grade papers, to explain again and again a concept to the throng. It exhausts me to write appealing lesson plans, to work alongside and often in spite of parents and faculty. If I think too deeply about the public school system, it’s easy to get depressed, to throw up my hands. To quit and use my skills elsewhere.

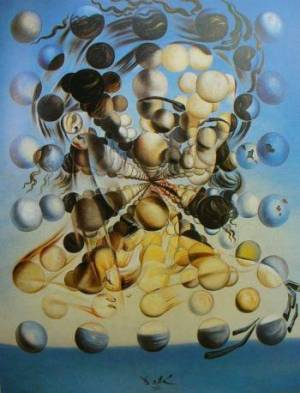

"Galatea of the Spheres" by Salvador DalíBut the morning has come, and I’m back. I teach my students about Hispanic and Latino painters. I show them Velazquez, Botero, Dalí, and Goya. These same riotous children discuss the uses of color, light and dark, on the canvas and are entranced. Through the paintings we consider various ways of looking at the world, through cubes, history, abstract form, and the color blue. I work too late in the evenings, and I know my alarm clock will ring too early in the morning. I will struggle to get out of bed an hour early to create my own work of art through words. I too, will be affected by the lie. It tells me to roll over and go back to sleep – that nothing I can create will be worth that extra hour of rest. But my students remind me, even as they tire me out: it’s my job as the artist to be present. I cannot fear the depths of the wretched because I must search out the lovely and show it to the world. Even when I fail out of fear I must try to say, “Here is something beautiful. Exchange it for your bloody fingerprints.”

"Galatea of the Spheres" by Salvador DalíBut the morning has come, and I’m back. I teach my students about Hispanic and Latino painters. I show them Velazquez, Botero, Dalí, and Goya. These same riotous children discuss the uses of color, light and dark, on the canvas and are entranced. Through the paintings we consider various ways of looking at the world, through cubes, history, abstract form, and the color blue. I work too late in the evenings, and I know my alarm clock will ring too early in the morning. I will struggle to get out of bed an hour early to create my own work of art through words. I too, will be affected by the lie. It tells me to roll over and go back to sleep – that nothing I can create will be worth that extra hour of rest. But my students remind me, even as they tire me out: it’s my job as the artist to be present. I cannot fear the depths of the wretched because I must search out the lovely and show it to the world. Even when I fail out of fear I must try to say, “Here is something beautiful. Exchange it for your bloody fingerprints.”

Jessica Eddings-Roeser is a writer and teacher of public school. She enjoys snuggling with her family members and pretending like she lives in Spain. She loves her dog, the environment, well-written songs, and her husband. She received a BA from the University of Texas with a degree in Spanish and English and has an MFA in fiction from Seattle Pacific University.